Speaking Tongues Are Actively Braced

Motivation

The term “bracing” describes speech production where the tongue is in contact with the teeth or palate. While “bracing” implies active mechanical support rather than mere contact, tongue bracing has typically been both defined and measured strictly in terms of contact.

This view can be attributed, in part, to the dominant representation of the vocal tract in midsagittal cross-section in the phonetics literature. Viewed only in the midsagittal plane, the tongue may appear to function as if unconstrained by interactions with surrounding lateral structures, more like a free-floating tentacle.

As such, a more holistic view of the tongue and its relationship with its surroundings in speech is required. We seek answers to questions both of basic description (e.g., How often is the tongue in contact with surrounding structures?) and of deeper function (e.g., What is the purpose of such contact?). However, the question of function only makes sense if contact is active and effortful (rather than passive or incidental).

Overview

We test the strong hypothesis that tongue bracing is both pervasive and effortful in speech. This hypothesis generates the predictions that 1) bracing should be maintained (nearly) continuously throughout running speech and 2) bracing is not incidental, but rather achieved and maintained via active muscular control.

1. Pervasiveness of Lateral Bracing

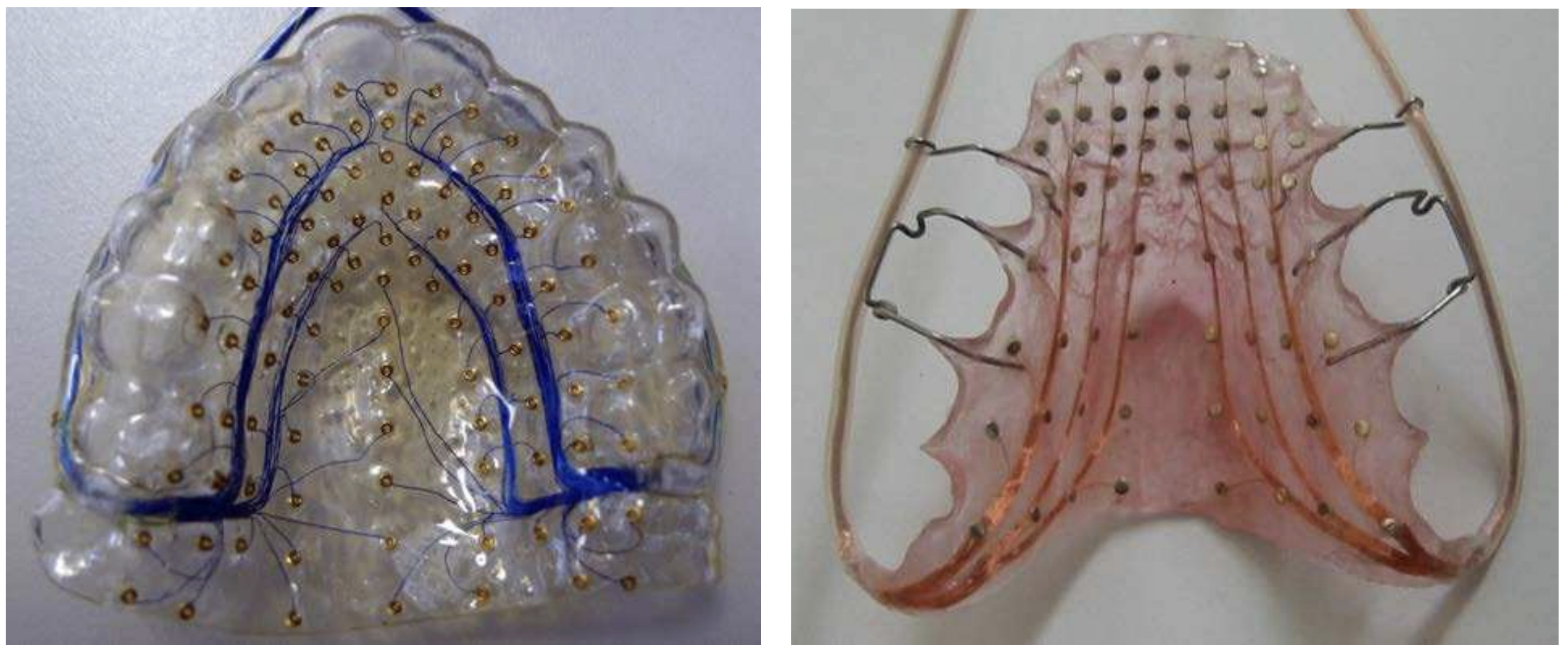

Electropalatography (EPG) uses a false palate with contact-sensitive electrodes. When placed in the mouth during speech, tongue contact with the electrodes is recorded in real time. However, a typical EPG palate (right in the figure below) lacks electrodes on the teeth, and so cannot record lateral bracing. We use the Kay EPG (left in the figure below) in this work to overcome this limitation.

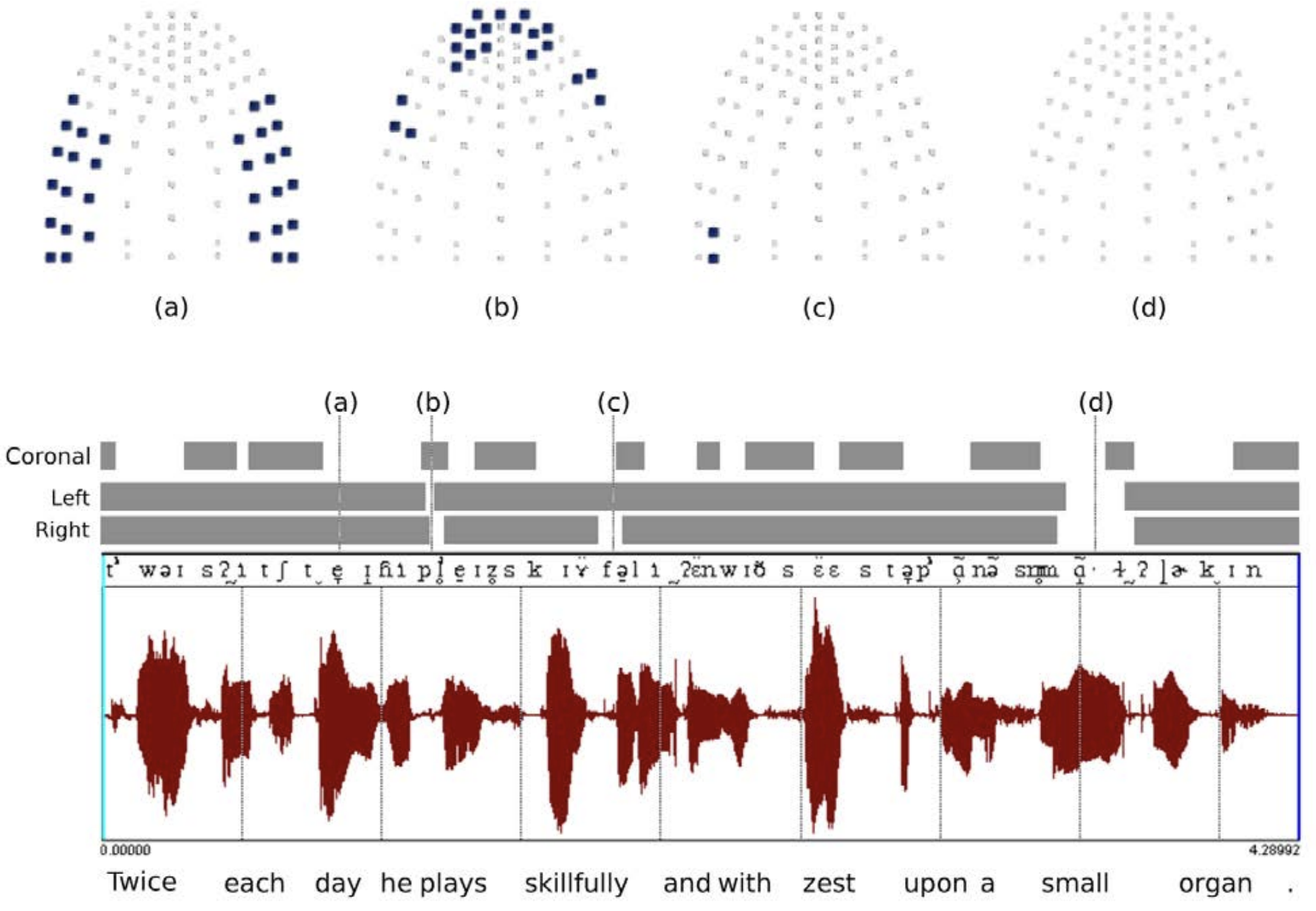

The Kay EPG produces results as seen in the figure below. Notice that left and right (i.e., lateral teeth) bracing is nearly continuous, whereas coronal (i.e., front teeth) bracing is more sparse.

Despite, the improved contact area of the Kay EPG, we still lack data on soft tissues, such as the pharyngeal structures (back of the throat). As such, during the low vowel /a/ in the word “small” in (d) the figure above, we observe no tongue contact at all.

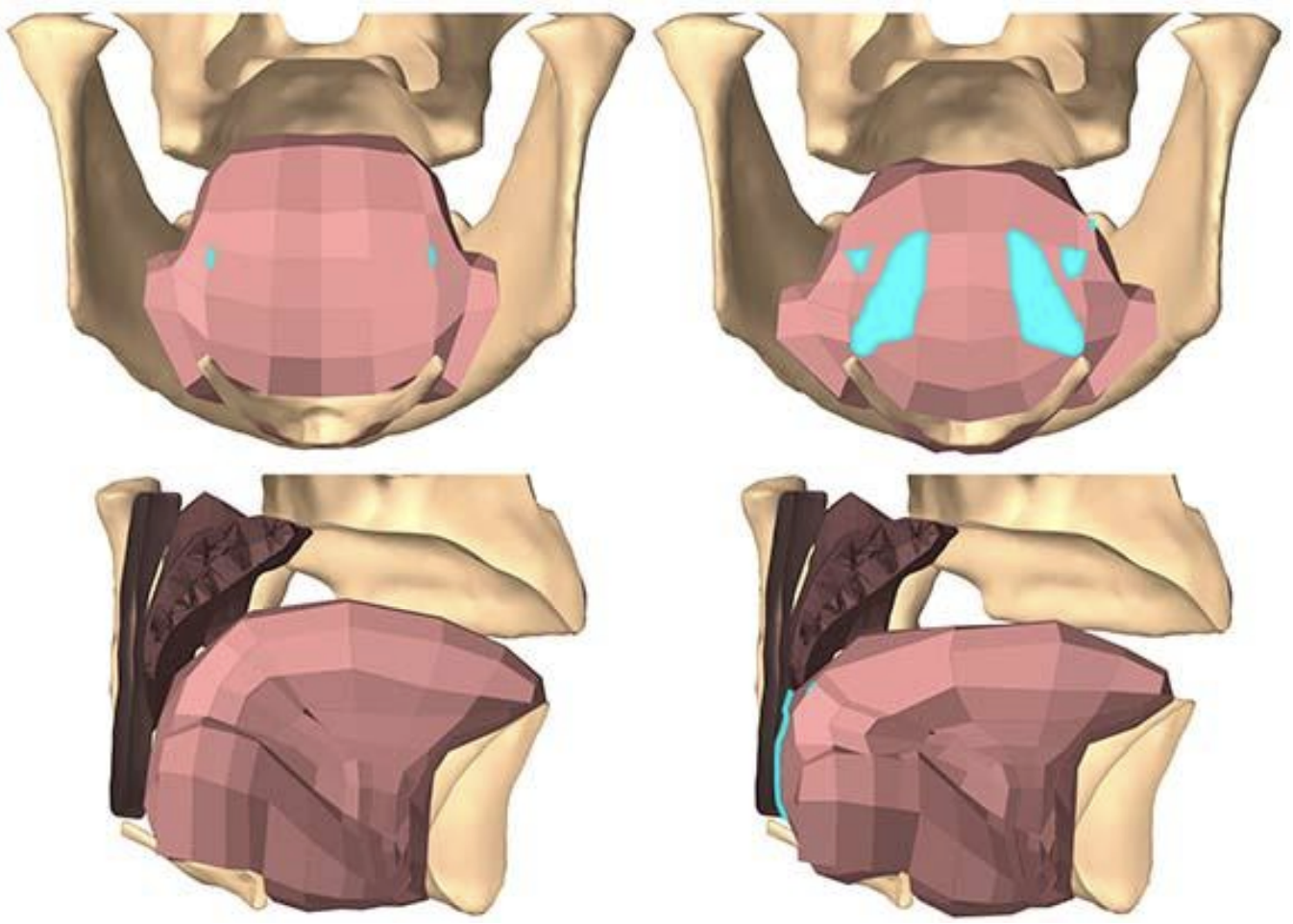

To overcome this limitation, we conducted 3D biomechanical simulations of the vocal tract using ArtiSynth, an open-source biomechanical simulation toolkit. Our simulations show that a tongue at rest makes no contact with the teeth or palate, but also makes essentially no contact with the back of the throat (left in the figure below). In contrast, during low vowels, such as /a/, the tongue still makes no contact with the teeth or palate, but it does makes contact with the back of the throat (right in the figure below).

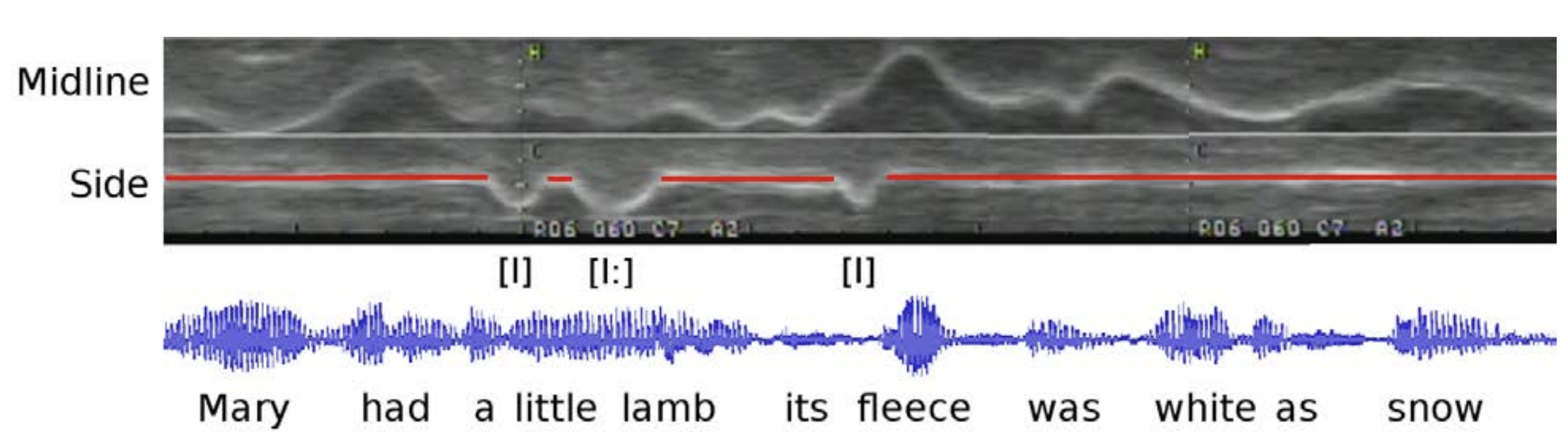

As additional evidence of the pervasiveness of lateral bracing, this ultrasound shows that the midline of the tongue moves continuously during speech, whereas the side of the tongue nearly always in a fixed and braced position against the teeth, except during /l/ sounds.

2. Effortfulness of Lateral Bracing

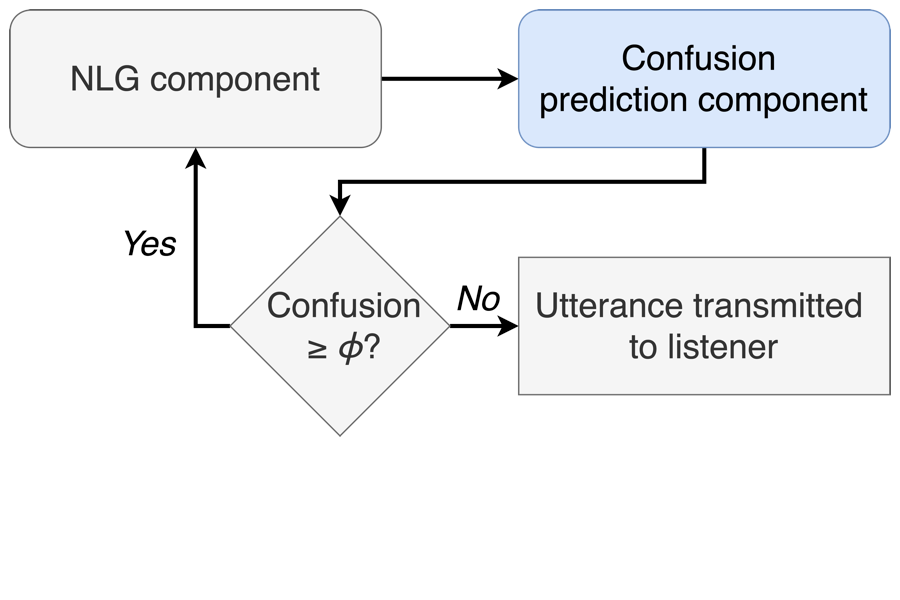

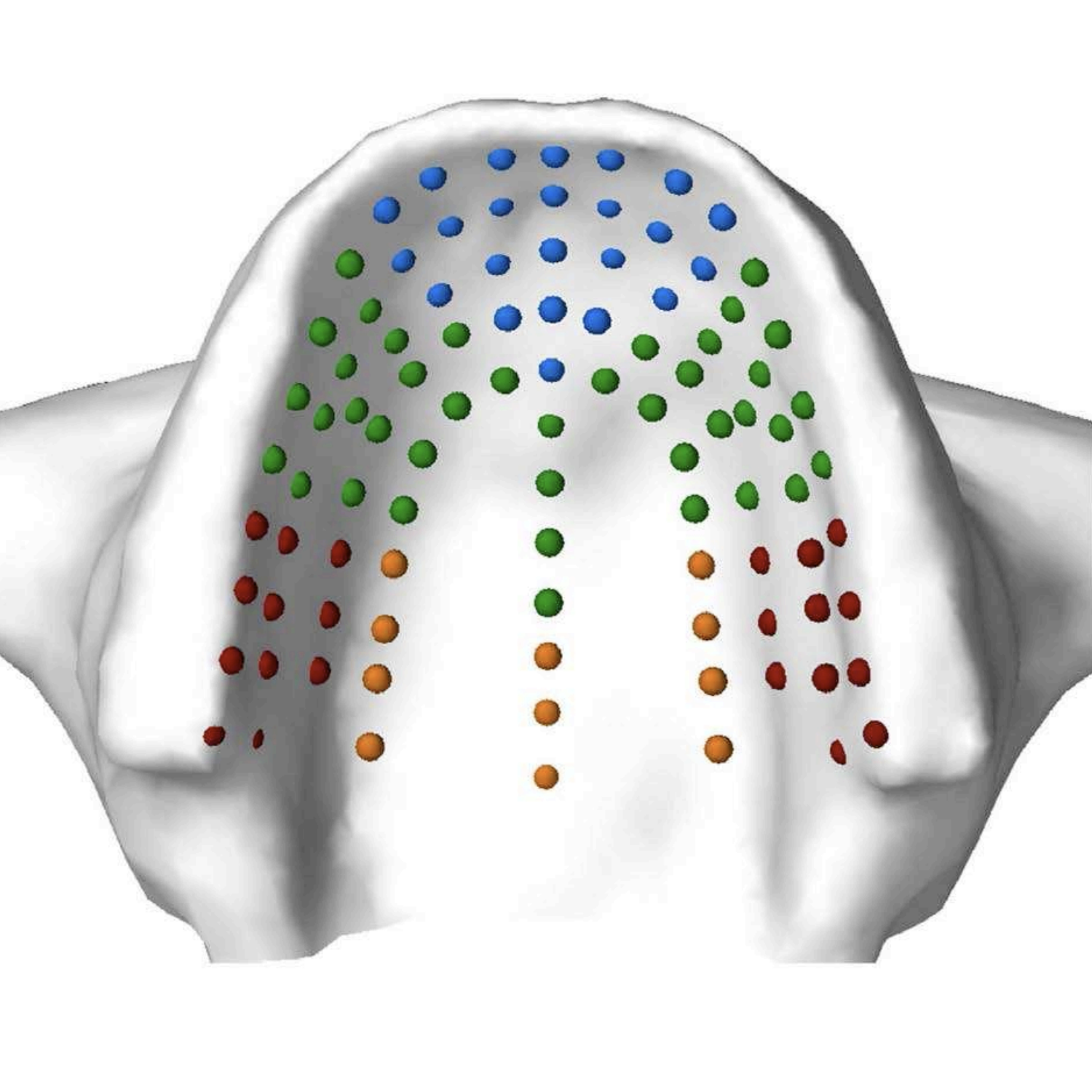

We constructed a virtual EPG that fits onto the palate of our ArtiSynth vocal tract model (see figure below).

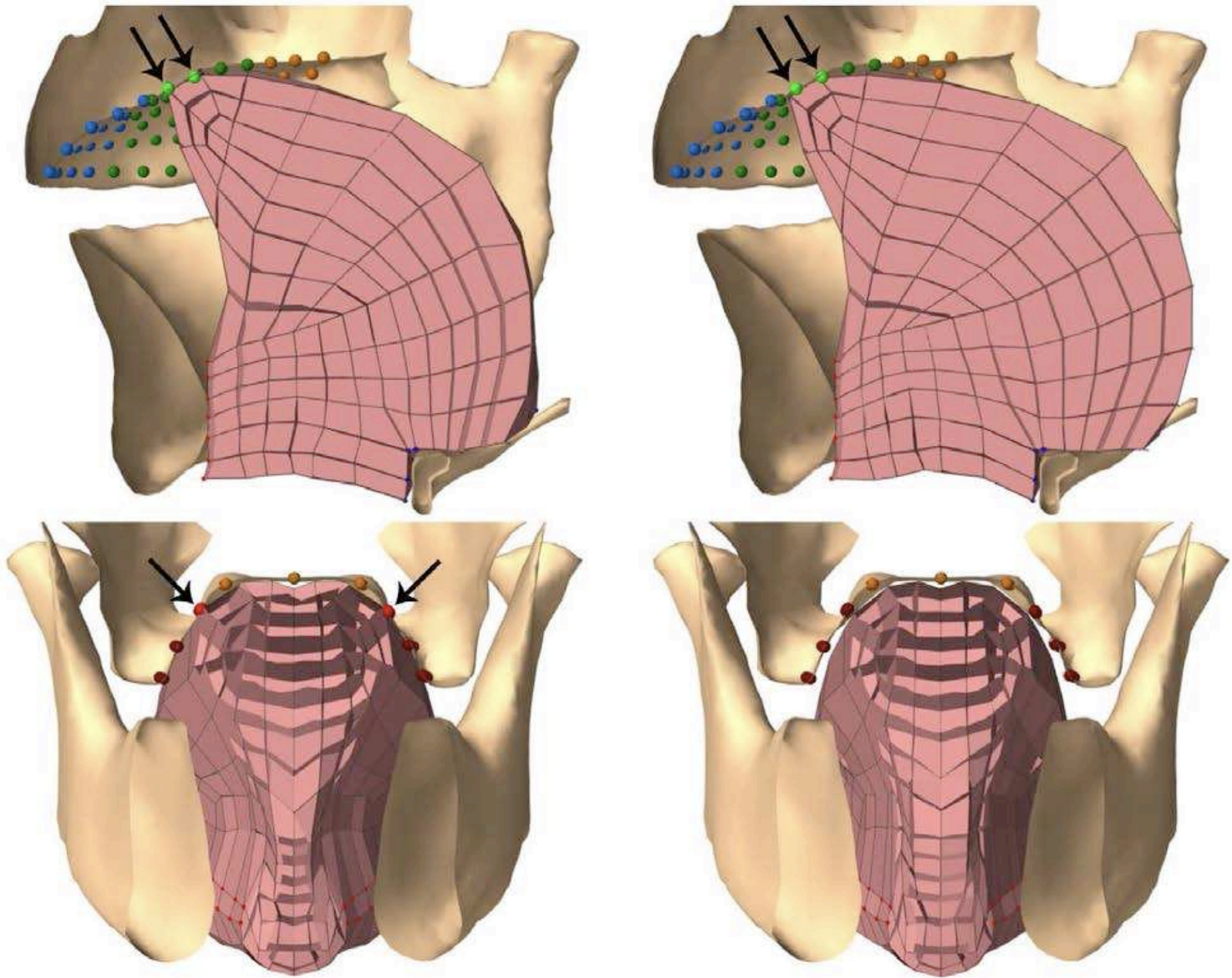

Using this virtual EPG, we placed the tip of the tongue in the same position on the simulated palate (top row in the figure below). However, in the left column, the tongue is additionally in contact with the lateral teeth, whereas it is not in contact in the right column.

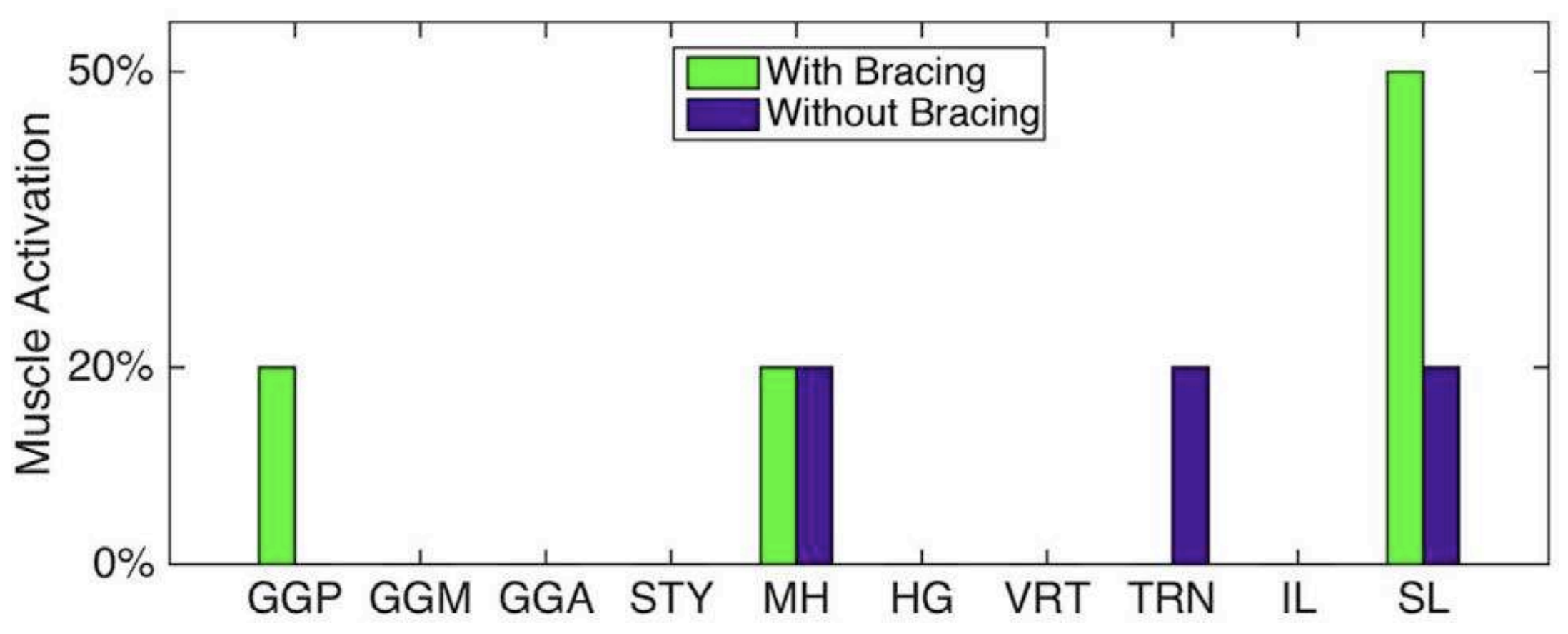

The braced position requires significantly more activation of the superior longitudinal (SL) muscle, indicating that contact is achieved only through active bracing, which is an effortful process.